Steve Katon

Last November and December, Steve Katon travelled to Berlin and the towns of Oranienburg and Pirna to conduct research for his Arts and Humanities Research Council Midlands4Cities-funded PhD in creative and critical writing. Here are some of his reflections.

My PhD project looks at the underrepresentation of disability in children’s literature. The creative part involves me writing a novel set in Nazi Germany covering the state-sponsored murder of disabled people which took place under the codename Aktion T4.

Thanks to funding from the AHRC, researching the novel took me to the Jewish Museum in Berlin, Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp and the permanent memorials of the Aktion T4 killing centres at Brandenburg an der Havel and Pirna-Sonnenstein. I talk about these in a blog post that I wrote for Nottingham UNESCO City of Literature to coincide with Holocaust Memorial Day.

Below, I will focus instead on some research I undertook on bookshops that were trading in the period I am writing about, and in particular the fate of Jewish booksellers of the time. The main character in my novel is Friede, a girl with Down’s syndrome, who has been adopted by Bernard, a writer and bookseller, and his sister Dorothy, a doctor. Both siblings are Jewish.

A large part of my visit to Berlin was to help me to build a picture of Bernard’s bookshop and gain insights into the life of a Jewish bookseller in the years leading up to the war. To begin, I therefore visited the excellent Landesarchiv, which holds documents and photographs of the German capital’s institutions, businesses and residences.

I had corresponded with Carmen Schwietzer, the deputy director of the archive, before my visit. When we met in person, Carmen very kindly helped me to identify several Jewish booksellers in the districts of Charlottenburg and Schöneberg that were trading in the 1930s. While at the archive I looked at the original records of these. As you may imagine, many of the files are heavily administrative in nature and, as they were written by biased perpetrators, are not particularly revealing of their crimes. An example below relates to a Jewish bookseller called Willy Flanter, who, even after he had been banned from selling books, still fought to stay in business. The letter on the left shows his tenacity to continue trading by attempting to re-register his business as a manufacturer.

It was a privilege to study this archive. All the same, after many hours of poring through documents, I was keen to get out and explore the streets. And on a sunny Saturday morning I did just that.

A hero of Berlin bookselling is the so-called Lioness of Kurfürstendamm, Marga Schoeller. She started selling literature in 1929 and, though no longer in its original location, her shop is still trading today.

Schoeller, who is not Jewish, welcomed writers, actors, academics and students to her shop, forming, as she called it, the anti-Nazi intelligentsia of the city. She bravely reserved a good stock of banned material in a secret cellar, which was only opened for her most trusted customers. I am almost certain a fictional version of the Lioness will claw her way into my novel. If you find yourself in Berlin, I highly recommend a visit. The staff were friendly and helpful, and I could have stayed much longer than I did. But I had work to do.

When looking for inspiration for the exterior of my fictional bookshop, the name of one premises leapt out at me: Willy Cohn’s Book Corner, in Schöneberg. I found the location of the shop, which is now a rather nice cafe. Stopping here for refreshments, I imagined how my fictional characters might have inhabited it in the 1920s and 1930s.

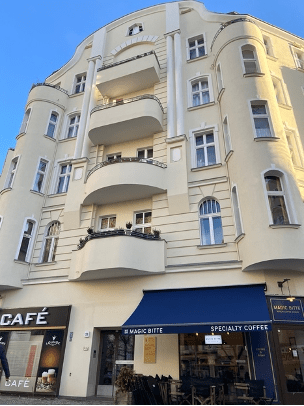

I would have to rely on old photographs to get to grips with the layout of the premises when they were bookshops. But then I got lucky at the address of a 1930s Jewish bookseller called Ernst Hesse. There were no signs of a shop frontage: this is a block of apartments – though the architecture clearly predated the war. I imagine this was Hesse’s trading address and the door to the communal entrance had been left open. Looking inside, I was treated to the sight of an opulent hardwood handrail, some gorgeous interior doors and an original ceramic-tiled floor. Perhaps the inside of my fictional bookshop and the stairs to my character’s apartments will look something like this.

But what of the booksellers who lived in these places? How are they commemorated? There is an ongoing initiative known as the stolpersteines: 10cm square blocks set into the pavement outside the last known residences of victims of the Nazis. More than once, I found at my feet details of how their stories ended. Here are those of Willy Flanter and another famous Berlin bookseller called Arthur Cassirer, and their families.

I will end by saying your German may be better than mine, but if not, it’s perhaps enough to know that the word ermordet, etched into many of these stones, simply translates as ‘murdered’.